Ecocide: The Destruction of the Environment and Indigenous Peoples

- Linda Zheng

- Apr 22, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2022

Protesters against Brazilian President Jair Bolosonaro's ecocide of the Amazon Rainforest Photo Credit: Thierry Monasse/Getty Images

By Linda Zheng

For decades, environmental activists and indigenous people have pushed for ecocide, or the mass destruction of the environment, to be an internationally recognized crime. There are currently only four internationally recognized crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression, but an amendment to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) could make ecocide the fifth international crime. Ecocide has occurred throughout history and particularly impacts indigenous communities. This Earth Day, the legacy of ecocide and its destructive impact on indigenous groups brings a much-needed perspective to the climate change debate.

The term and concept of ‘ecocide’ first originated in the 1970s in the wake of the mass devastation left behind by the deliberate targeting of the environment during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was one of many “Rainbow Herbicides” used by the United States military in their campaign to defoliate forests and mangroves in Vietnam that were providing cover and food for enemy forces. Agent Orange, in particular, accounted for 60% of the 72 million liters of herbicides sprayed across Vietnam during the war. Over 3,100,000 hectares of land and forests were defoliated in Vietnam, resulting in heavy contamination of soil, deforestation, and devastating loss of biodiversity. In addition to harmful environmental effects, Vietnamese and U.S. soldiers who were exposed to Agent Orange faced major health issues like cancer or had children with birth defects.

The first major push to recognize ecocide began in 1972 at the United Nations Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment. Olof Palme, the then Prime Minister of Sweden, spoke openly of the Vietnam War as ecocide. Since then, several attempts have been made to bring international awareness to this crime. In 1998, during the formal establishment of the ICC, early drafts of the Rome Statute included the crime of environmental destruction. This crime was ultimately removed after pushback from the U.S. From 2010 up until her death, Scottish barrister Polly Higgins campaigned for ecocide to be recognized as a crime against humanity.

In June 2021, a global team of legal experts drew up a formal definition of ecocide and submitted it to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in a historic push toward defining and formally recognizing ecocide as an international crime. According to Stop Ecocide International which led this initiative, ‘ecocide’ is defined as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.”

Unlike the current international crimes recognized by the ICC, ecocide is uniquely ecocentric (i.e. focused on the environment) rather than anthropocentric (i.e. human-focused). Despite this, it is clear from cases throughout history like the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam that people living in regions impacted by ecocide are always affected by the destruction of the local environment. Of particular concern are vulnerable groups like indigenous communities who share a close relationship with the environment and subsequently depend on its resources to survive. Indigenous peoples account for only 5% of the world’s population yet they effectively manage land that holds 80% of the planet’s biodiversity. Indigenous peoples are also among the first to face the direct impacts of climate change, but the last to be consulted when considering environmental concerns.

Indigenous activists oftentimes risk their lives to protect the environment. A recent report shows that of the 227 land and environmental defenders killed in 2020, one-in-three were from an indigenous community. The report also suggests that as the effects of climate change worsen, so will violence against people protecting the environment. In 2020, violence against environmental activists took place almost entirely in the Global South, with an overwhelming majority of attacks against land and environmental defenders occurring in just three countries—Colombia, Mexico, and the Philippines.

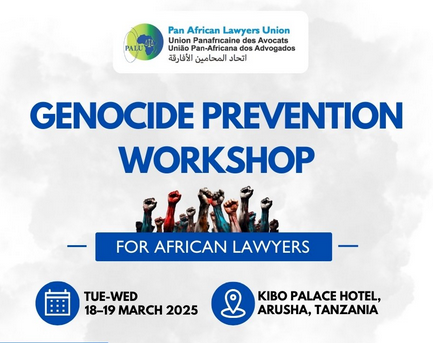

In Brazil, indigenous activists are leading the charge against the destruction of the Amazon rainforest which has reached near-record levels since the election of Jair Bolsonaro, the President of Brazil. From August 2020 to July 2021, over 8,700 square kilometers of forest cover the size of Puerto Rico was destroyed in Brazil. The Amazon rainforest is home to 30 million people, including 1.6 million indigenous peoples who are currently being threatened by deforestation and raging wildfires that have spread to their ancestral lands. Brazil’s far-right president has destroyed environmental programs and enacted a series of anti-Indigenous policies that have opened protected lands to exploitation by agribusiness, mining, and large-scale infrastructure projects. With no signs of stopping, indigenous peoples in Brazil have been protesting and working with organizations to take action against Bolsonaro. To combat ecocide in Brazil, an indigenous organization has requested that the ICC investigate Bolsonaro’s actions saying, “We believe there are acts in progress in Brazil that constitute crimes against humanity, genocide, and ecocide.”

Climate change is one of the greatest issues facing humanity today, and yet ecocide is still not recognized as an international crime. Advocacy for the recognition of ecocide has persisted since the 1970s and as climate change continues to shape the diverse landscapes of our world, it is clear that advocacy will only get stronger. At the forefront of this advocacy work are indigenous peoples whose livelihoods are interwoven with the environment and whose sacrifices continue to protect the planet and its biodiversity.

Linda Zheng is an Alliance Coordinator and Communications Director at Genocide Watch

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Genocide Watch.

.png)

Comments